Youth Here Doesn't Seem to Know about the Disappearance of the Old School.

Hip-Hop DJs and the Firesign Theatre

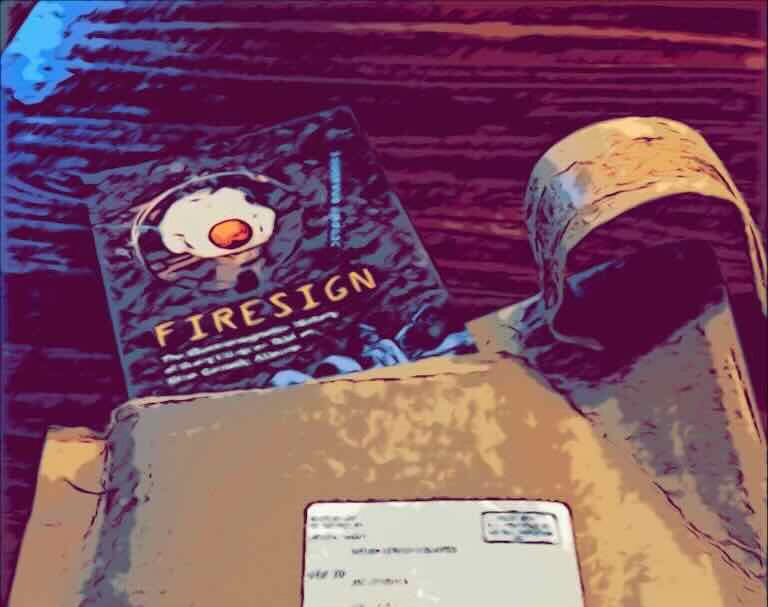

It was exciting this week to start getting selfies and pics of Firesign starting to arrive in mailboxes. The official release date is October 29, but it’s already shipping for people ordering from the IndiePubs / University of California Press site.

Today I’m posting an excerpt from the coda of Firesign, where I trace some of the Firesign Theatre’s afterlives, from the 1976 Papoon for President campaign to the Church of the Subgenius to (briefly) Negativland, to — in this case — the thirty-year history of Firesign samples on hip-hop records.

A complete (or nearly complete!) discography of these records is included as Appendix B of Firesign. I’ve also made a near-complete playlist on YouTube here. If I’ve missed any (or if anyone knows the missing Giant Rat sample!) tell me in the comments.

Finally, I’ll be having a book party in Chicago on November 8 where DJ T. Tauri will be spinning a set of these Firesign-sampling records, as well as vintage house and downtempo. If you’re in the area, message me directly for details. It’s going to be a fun night and I’d love to see you.

from the run-out groove of Firesign: The Electromagnetic History of Everything as Told on Nine Comedy Albums

What made possible work like the “culture-jamming” bricolage of Negativland's late-eighties albums were the newly affordable digital samplers like the Akai S900 and MPC60, the E-MU SP1200, and the Ensoniq EPS. These same devices were at this very time enabling what would become a far more widely influential revolution, born in the underground, in the world of sample-based hip hop. As Tricia Rose wrote in her foundational 1994 study, the digital sampler is the “quintessential rap production tool,” contributing instrumentally to what has come to be known as the genre's late-1980s “golden age.”1 It was in this context that the Firesign Theatre’s Columbia albums began to be given a new and different life — “alternative lives and alternative meanings” as Rose describes the fate of the sample — though it is one that seems on the whole to be surprisingly sympathetic with Firesign’s project, albeit obviously formed by its own cultural priorities and listening practices.2 Like the DJs who sampled them, we might say, the Firesign Theatre were critically engaged media artists, deeply conversant with the issues of their time, drawn simultaneously to the technological vanguard and to its historical imbrication. In musicologist Tom Perchard’s phrase, hip hop producers were engaged in a “critical, musical-historical discourse […] in which contemporary creative agency was ever intertwined with representations of and relationships to the past, both productive and problematic.”

Fireisgn’s Columbia albums have been extensively sampled by the most recondite DJs in the history of hip hop, from DJ Mark the 45 King (on the Chill Rob G track “The Power,” 1989) to the Freddie Gibbs, Curren$y, and Alchemist collaboration “Location Remote” (from the album Fetti, 2019). Taken on its own terms, this discography is testimony both to the aesthetic evolution and to the ethical consistency of sampling practices across thirty years. With respect to the latter, across the thirty-odd tracks I have found, there is no sampled phrase that appears more than once (the one exception being Pastor Flash’s irresistible “I’m high, all right” from Don't Crush That Dwarf), and every album other than The Giant Rat of Sumatra has been sampled at least once (though I will testify to having heard that one sampled, too, in a trip hop track at a coffee shop in Philly). This suggests the importance of originality, as DJ Mark the 45 King confirmed in an interview the same year he was producing Chill Rob G: “People look up to me because I'm looping up records that haven’t been used before. I have to buy all the breakbeats records to know what not to use.”3 And it also suggests the importance not only of knowing but of performing knowledge of the field through cross-reference.

In what appears to be the first time a record sampled the Firesign Theatre, Mark the 45 King dropped the voice of the hologramic President in I Think We're All Bozos on this Bus in a track that took its beat and its title from Snap!'s 1989 track “The Power.” Two years later, the “War Mix” of Steinski and Mass Media’s “It’s Up to You” — an up-to-the-minute protest of the first Gulf War — answered by sampling Don't Crush That Dwarf’s Deacon E.L. Mouse (“Is it going to be all right?”) as the first voice in a devastating tape collage of phrases drawn from the speeches of then-president, George H.W. Bush. These began with Bush 1’s empty apothegm on the theme of democratic “power”: “We are Americans. Americans know power belongs in the hands of people.” Steinski and Mass Media’s samples cite their original sources, but they are also citations of the 45 King’s previous samples: the 45 King sampled Firesign’s robot president in a song called “The Power”; “It’s Up to You” samples the Firesign Theatre before the sitting president’s bloviations about the people's “power” as he prepared to declare war.

In these inaugural examples from the late eighties and early nineties, the technique is to use a relatively long sampled phrase at the start of a track, playfully or ironically setting the mood. On “Tha Frustrated N----” (1996) DJ Premier cuts up Ossman's lines introducing Nick Danger (“he walks again […] ruthlessly”) as an overture for Jeru the Damaga before the rapper begins his first lyrics; in his 1998 remix the classic track “Jazzy Sensation” by Afrika Bambaataa and the Jazzy 5 (1981), Steinski samples the courtroom scene in Don't Crush That Dwarf (“Youth here doesn't seem to know about the disappearance of the old school”) making a pun about old school hip hop out of the one the Firesign Theatre had intended about square culture’s indignation about hip youth culture (on an album where the “old school” of Morse Science literally disappears).

Famous (with his partner Double Dee) for the early-eighties sample collages “The Lessons,” Steinski was by then himself decidedly old school. And at that point, a new hip hop subgenre of turntablism — which elevated the musical role of the DJ, sometimes without a rapping MC — had begun to flourish both in New York City and on the west coast in LA and San Francisco. Originally released on cassette by Future Primitive Sound — an important SF space for turntablists including DJ Shadow, Cut Chemist, and Shortkut — the Presage Collective's mystically paranoid Outer Perimeter record represented another stage of sampling practice in which a single record might be sampled extensively to compose a kind of narrative commentary running over and through the course of an album.4 In this case Presage's Mr. Dibbs and DJ Jel liberally plunder Firesign's Everything You Know is Wrong, transforming an album that genially spoofs New Age enthusiasms like aliens, alternate histories, and psychokinesis into its obsessional and conspiratorial twin: “Presage is a warning brought to you by Mr. Dibbs, DJ Jel and MC Dose of the 1200 Hobos.”

By the twenty-first century, virtuosic producers like J. Dilla and Madlib embedded shorter, harder to identify Firesign samples as more deeply occulted elements within the mix. Madlib, who together with J. Rocc went to meet the Firesign Theatre at one of their last performances, has sampled the Firesign Theatre more than anyone, combining the heteroclite assemblages of west coast turntablism with golden age skits on albums like Madvillainy, a collaboration with MF Doom that included numerous characters and a loose narrative.5

The historian Seth M. Markle has recently examined Madlib's 2010 album Beat Konducta in Africa, understanding its vast array of African and Africa-themed samples as a “‘dialogue and commentary’ on the historical significance of African and African diaspora music and pan-Africanist struggle.” In this eye-opening account, Madlib is presented as “the hip hop DJ as black archaeologist,” echoing Tricia Rose's earlier account of sampling as “a means of archival research, a process of musical and cultural archeology.”6 An obvious riff on the practice of “crate-digging,” the appearance of this archaeological metaphor is notable because of its importance in a different context in this book, where I have tried to make a case for the Firesign Theatre as practicing a kind of media archaeology avant la lettre. But it also raises the question of whether more can be inferred about the place of the Firesign Theatre in hip hop’s self-selected archive.

To state the obvious, as monuments of a literary white stoner comedy, these albums could not have the same significance for black audiences that the African sources comprising the 2010 Madlib album would have, to say nothing of the heavily mined and culturally resonant sources like James Brown, Parliament, and seventies jazz. It would nevertheless still be possible to agree with the musicologist Tom Perchard, who respectfully qualifies the historicist argument by suggesting that “while aspects of cultural memory were in play [in hip hop's sampling of jazz recordings], so too were self-interested exploitations of the forgotten and the unknown”?7 Although Steinski, Premier, and the 45 King may have heard the Firesign Theatre as a part of their generation's discography, later DJs like Madlib, J Dilla, and Alchemist would have had to have discovered them among their parents' collections (Madlib’s parents having been musicians themselves) or in the used bins.

There is no single answer to this question, but there is further suggestive evidence in the history of the reception of hip hop at the dawn of its golden age. When De La Soul’s first album, Three Feet High and Rising, appeared in 1989, the Village Voice’s Greg Tate, the NME’s Sean O'Hagan, and the cultural critic Mark Dery (coiner of the term “Afrofuturism”) all compared the group to the Firesign Theatre.8 This was no doubt in part inspired by the fact that Three Feet High and Rising both played with the image of psychedelia and was also very funny, but as Dery insisted, the Firesign Theatre's records were “more semiotic guerrilla warfare than conventional comedy” and De La Soul’s debut was “equally surreal.”9 Dery was pointing out the way, anticipating turntablism, the record’s huge range of samples (not Firesign but Liberace, Johnny Cash, and Steely Dan alongside the Detroit Emeralds, Barry White, Parliament, and Michael Jackson) itself resembled the enormous storehouse of references comprising any five minutes of a Firesign Theatre album (Kent State, the MGM Auction, Candide, televangelism).

Tate and Dery were also picking up on the phenomenon of the hip hop skit — a game show pastiche and other scenarios runs through Three Feet High and Rising — and the way that a kind of theatrical space might not only sit between songs but also be incorporated as a fictive space within a song. This was an idea that was not unique to De La Soul, but could be found throughout contemporary recordings by The Pharcyde (“Officer”), Public Enemy (“More News at 11”), Queen Latifah (“Mama Gave Birth to the Soul Children”), and many others. This tradition of diegetic space went back to the presampling era on tracks like the Last Poets’ “On the Subway” (1970) which verbally created the space of a New York City subway car setting a dramatic context for Alafia Pudim’s poem about a white man's failure to recognize him as they shared a subway car alone. The Last Poets’ collectively, verbally produced architecture on this cut resembles the improvised tracks released on the Firesign Theatre’s 1972 Dear Friends, which notably also included the collaboration of a DJ and engineer, the Live Earl Jive.

Combined with the layering effects of multitrack recording (and, in rap music, sampling) these parallel discoveries became ways of being “two places at once,” in the radically realized comic dramas of the Firesign Theatre and the revolutionary musical worlds of golden age hip hop. Is it too much to assume that DJs with ears as big as Madlib's would have intuited a parallel achievement? In Rose’s early account rap music is, in terms sampled from Marshall McLuhan's student Walter J. Ong, a “complex fusion of orality and postmodern technology […] fundamentally literate and deeply technological.”10 In another register this was the same fusion the Firesign Theatre performed in their own work.

Unsurprisingly, maybe, from across this diverse array of samples from the Firesign Theatre's catalog, there is not one example that includes the Firesign Theatre’s adoption of racialized voices (the closest being Wolfman Jack’s cameo on Ossman’s solo album How Time Flys — sampled by both J. Dilla and Madlib — Jack having made his name by appropriating the vocal style of black DJs for his famous border radio show in the 1960s). Rather, it seems much more plausible that the DJs who discerningly sampled the Firesign Theatre — whether they were evidently fans or where the attitude is more inscrutable — heard the Firesign Theatre's voices as critical parodies of whiteness (their samples resembling the verbal marking practices of comedians like Rudy Ray Moore and Richard Pryor, who would parody white voices). Placed in the service of a black music, this recontextualization was an appropriative and interpretive act that may have drawn attention, critically, to the Firesign Theatre’s arrogating aspiration to heteroglossia. Firesign would not have heard their own work as being, in the first instance, a critique of whiteness. But precisely because their own work was critical and parodic, they no doubt would have recognized that reading and approved the purposes their work has since been made to perform.

Tricia Rose, Black Noise: Rap Music and Black Culture in Contemporary America (Hanover, NH: Wesleyan UP, 1994) 73.

Rose, Black Noise, 90.

Mark the 45 King quoted in Perchard, “Hip Hop Samples Jazz,” 290.

On the SF turntablist scene, see Mark Katz, Groove Music: The Art and Culture of the Hip-Hop DJ (New York: Oxford UP, 2012) 127-52, 179-213.

Richard Metzger, email to the author, 31 Aug. 2021.

Seth M. Markle, “The Hip-Hop DJ as Black Archaeologist: Madlib’s Beat Konducta in Africa and the Politics of Memory,” Politics of an Anticolonial Archive, ed. Shiera S. el-Malik and Isaac A. Kamola (London: Rowman & Littlefield, 2018) 208; Rose, Black Noise, 79.

Perchard, “Hip Hop Samples Jazz,” 290.

Greg Tate, "Yabba Dabba Doo-Wop," Flyboy in the Buttermilk: Essays on Contemporary America (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1992) 137-41; Sean O'Hagan, “De La Soul: Three Feet High and Rising (Big Life LP/Cassette/CD).” New Musical Express, March 18, 1989. Rock’s Backpages.

Mark Dery, “Digital Underground, Coldcut and De La Soul Jam The Beat," Keyboard (March 1991) Rock’s Backpages.

Rose, Black Noise, 85, 95.