Lord Buckley

I say it is the duty of the humor of any given nation in time of high crisis to attack the catastrophe that faces it in such a manner as to cause the people to laugh at it in such a way that they do not die before they get killed.

— Lord Buckley, H-Bomb, 1950s

For those unfamiliar, Lord Buckley was the unlikely stage persona of an American comedian (Richard Myrle Buckley) who pretended to be a minor British aristocrat whose shaggy improvised disquisitions on such topics as Jesus (“The Nazz”), Shakespeare (“Willie the Shake”), and the Marquis de Sade were delivered in a self-styled argot that apparently combined the amphetamine-fueled jive of beatnik jazzers with a touch of arch British nobility. Among his fans was Sly Stone, who in the years before the Family Stone used to begin his Bay Area radio shows with quotations and impressions of Lord Buckley’s bits. Here’s a clip of Sly Stone riffing on the “The Nazz” on the Dick Cavett show in 1971:

The Firesign Theatre were certainly fans of Lord Buckley too. There’s a touch of Buckley’s hip riffing in Peter Bergman’s Radio Free Oz persona — the radio program that gave birth to Firesign — and bits from Buckley’s albums appeared on the air from time to time.

Lord Buckley died prematurely of a stroke in 1960, during a period when he was being hassled by the police over his cabaret license. The H-Bomb routine linked above was released on a posthumous compilation in 1969. I say it is the duty of the humor of any given nation in time of high crisis to attack the catastrophe that faces it in such a manner as to cause the people to laugh at it in such a way that they do not die before they get killed. Though still living under the shadow of mutually assured destruction, the Firesign generation would have heard those words in the contexts of the Vietnam War and the crackdown on dissent at home. Besides the formal example of riffing, Lord Buckley gave the Firesign Theatre the model of a comedy that could express fear, and be a resource against it.

Dark Firesign

One of the things that really surprised me, in fact, as I was doing the research for Firesign was how many contemporary reviewers understood the Firesign Theatre’s ostensibly funny albums as frightening. Sure there were several accounts of the “court jesters of the rock generation” variety (vide the New York Times’ “Why Do Kids Love These Four Zany Guys?”1). But far more common were appraisals like those of Robert Christgau (“profoundly pessimistic if you ignore its comic element”) or Greil Marcus (“[h]orrifying, death-dealing, life-enhancing”), and these reviews were also the most thoughtful and interesting ones.2

Here’s a selection:

“the underlying mood is permeated with death, dread, murder, insanity.”3

—Richard C. Walls in Creem on Waiting for the Electrician

“This isn’t as funny as their first record, but it’s heavier, much heavier, with more manifestations of media consciousness […]. [T]he side starts off satirizing a man giving a used car sales pitch, but soon the pitch is for a different product, the ultimate in a pre-packaged all-purpose consumer good: the product is Amerika, and it’s dirt cheap.”4

—Walls in Creem on How Can You Be in Two Places at Once“[T]here are many here among us who think that it's already too late, although I'm not one of them. But this record will send you coasting on gales of laughter to a very unpleasant realization: time is running out. The secret message of the Firesign's last album was that the United States had lost its gigantic war against fascism, the one the history books have come to call World War II. […] This time they want you to know for sure. […] How do we deal with a society like this? How does one remain human in it?”5

—Ed Ward in Rolling Stone on Don’t Crush That Dwarf“How do you respond? Isn't that, after all, the question they are asking. This is, to be sure, the Firesign's most explicit album? It's not funny, as I was informed even before I'd heard it - it's terrifying. […] What's even worse […] is that it's such an accurate portrayal.”6

—Dave Marsh in Creem on I Think We’re All Bozos on this Bus“The record requires no less than total concentration. Its power is astonishing: a friend played it over Christmas and found it impossible to talk to anyone afterwards.”7

—“Neill” in International Times on Bozos

Firesign’s first album was recorded during and about the so-called Summer of Love. But uncertainty among the Columbia brass meant that they would not begin tracking their second album until late 1968. That recording (How Can You Be in Two Places at Once When You’re Not Anywhere at All) was bookended on one side by the Chicago DNC, the suppression of Prague Spring, and the Tlatelolco massacre and by the inauguration of Richard Nixon on the other. (Coming in between was the 1968 election, which Nixon won with only 43.4% of the popular vote.)

The great majority of the Firesign Theatre’s classic Columbia phase would then take place in the context of the unraveling of the student movement, the neutralization of dissent, and the political hegemony of the next several years. Chicago, Kent State, COINTELPRO are all (among other things) present on Firesign’s albums, in mediated but unmistakable form. Taken together, the reviews from the rock press recognized this context, and they also understand the conceit that Firesign used to dramatize it: a rapidly changing technology and media environment had led to a more sober appraisal of the true outcome of the Second World War. 1969: “The President of the United States is named Schicklgruber.” 1970: “In other news, final steps was [sic] taken in or near Washington to secure the merger of the US Government with TMZ General Corp.” 1971: “Count us to be there, Jim, because if we’re lucky tomorrow we won’t have to deal with questions like yours ever again.” This, by the way, would also have been a fair summary of the 1973 novel Gravity’s Rainbow, something I’ll take up in a future post.

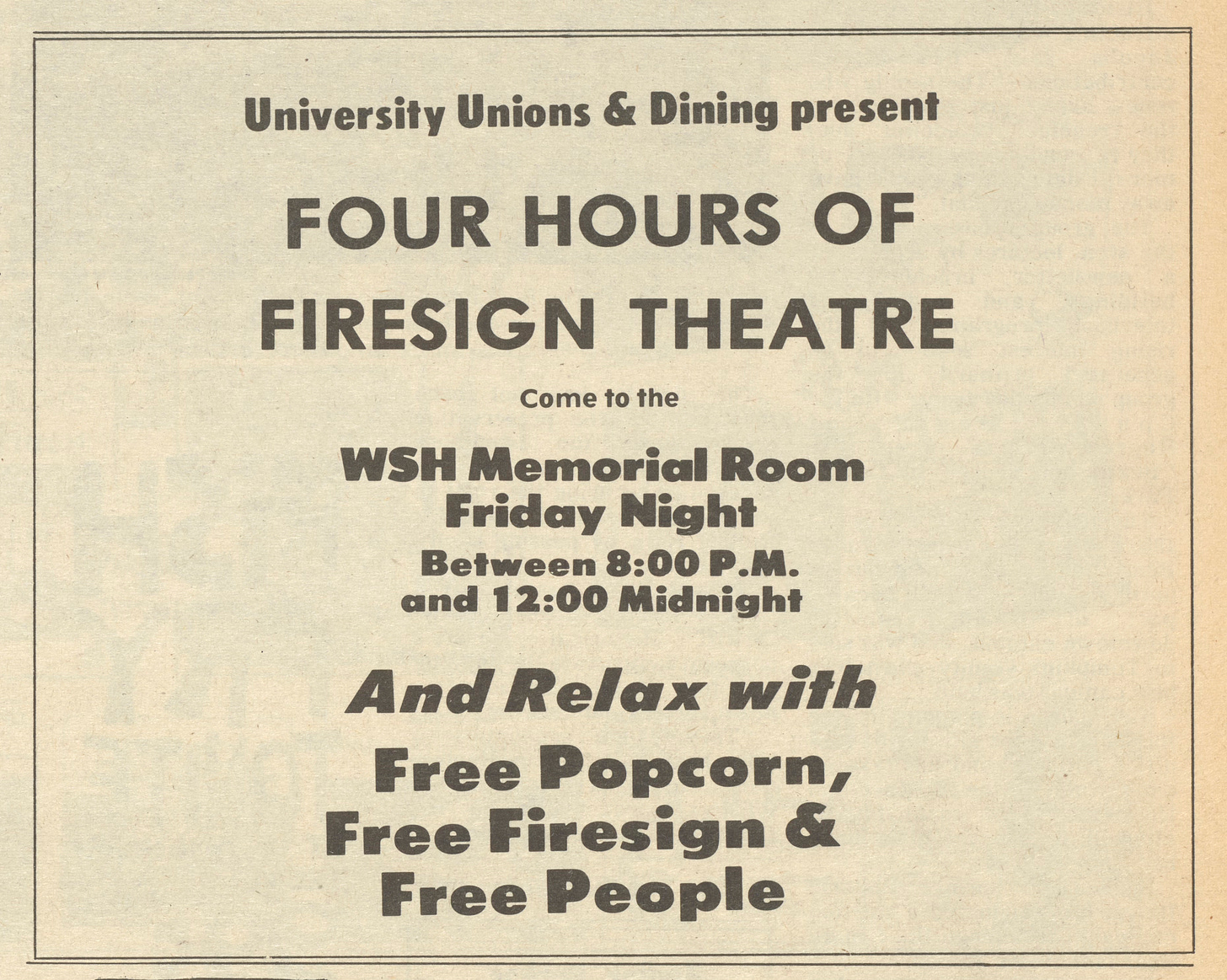

As the epiphanic, beautiful and bleak, conclusions of the Columbia records also indicate, though, Firesign’s albums were understood not only as frightening but as a place to go — something that was not only true for college kids by the way8 — something that could be experienced in conditions of privacy, at a time when all listening was not measured and quantified. The Columbia albums of course sound great in headphones, but it is surely not accidental that the conventional way of hearing them was in a dark room with other people. Sometimes that collective listening was more formal, as at the monthly listening parties I discovered Cornell’s student union sponsored in the early seventies. Heard in actual or simulated privacy, Firesign’s Columbia albums composed soundscapes that began as unsettling nightmares, and often ended in ambivalent desolation, a desolation that could sound soothing because it was not only a fearful image but an image of privacy. I’ve got a nickel wait for me. I see that you are a sailor. I guess this is the end. (Or is it only …?) No, it’s the end. There’s more than one way out.

Sontag’s Theory of Comedy, from the Happenings to Surrealism

Speaking of dreams, one thing I was not sure I would be able to make a convincing argument about in Firesign was the group’s claimed relationship to Surrealism. Along with Dada, Surrealism was an influence that they often insisted on, though usually without elaborating. Certainly there was space to make some second-order connections. Amid the mid-sixties vogue for Antonin Artaud — a fellow traveler and sometime member of the Paris Surrealists — Ossman translated a couple of short pieces for Jack Hirschman’s Artaud Anthology (City Lights Books). And, as I discovered, Ossman and Phil Proctor interviewed the “Mama of Dada” Kate Steinitz on Radio Free Oz in the summer of 1967, asking her about her partnership with Kurt Schwitters, watching the rise of fascism in their native Germany, and her escape to New York and Los Angeles in the late 1930s.

My friend Jonathan Eburne, an expert in Surrealism, was also helpful in pointing out the Paris Surrealist group’s attention to media, both wanting to intervene in the press and also through their politics of film spectatorship. But I was still not convinced that Surrealism, except as a weak synonym for dreamlike or simply “weird,” could be advanced as a way of understanding the Firesign albums. But then, finally addressing an embarrassing gap in my knowledge, I read Susan Sontag’s Against Interpretation and discovered her 1962 essay on Allan Kaprow’s Happenings.

The phenomenon of the Happening is itself directly relevant to the Firesign Theatre. As I’m sure I’ll discuss some other time (I have pictures), Peter Bergman spent some time in Amsterdam in 1964-65 and participated in one of Robert Jasper Grootveld’s performative Happenings, which took their cue from the Fluxus group and from Kaprow, and led to the formation of the activist Provo group in the spring of 1965.

Writing in 1962, Sontag was thinking about the Happenings she attended that year in the United States, occurring largely in the context of galleries and the art world. Noting that its key figures included a few musicians (Dick Higgins, La Monte Young), but were mostly artists then known as painters (Kaprow, Jim Dine, Yoko Ono, Claes Oldenburg, Carolee Schneemann), Sontag’s first observation is that the Happenings seemed at one level to be extensions of the monumental New York painting of the 1940s and 50s, abstract works that were “designed to overwhelm and envelop the spectator,” and which increasingly used materials other than paint (as in Robert Rauschenberg’s work).9 These Happenings realized “the latent intention of this type of painting to project itself into a three-dimensional form.”10

But this insight did not explain those artists’ apparent interest in disturbing or even abusing their audience, which to Sontag seemed to be “the dramatic spine of the Happening.” For this the most meaningful source was Surrealism, by which Sontag did not mean the tradition of museum painting associated with Salvador Dalí and René Magritte, but rather a “mode of sensibility which cuts across all the arts in the 20th century,” and included painting, poetry, music, cinema, the novel, and even architecture. “The Surrealist tradition in all these arts,” she wrote “is united by the idea of destroying conventional meanings, and creating new meanings or counter-meanings through radical juxtaposition (the ‘collage principle’).”11

Sontag goes on to specify that Surrealism, so understood, had been used both for the purposes of “inane, childish” wit and for tendentious social satire. But Sontag also discerns another, deeper vocation for the Surrealist tradition: “It can be conceived more seriously, therapeutically—for the purpose of reeducating the senses (in art) or the character (in psychoanalysis). And finally, it can be made to serve the purposes of terror.” And it is here, Sontag stresses, that the tradition of Surrealism “link[s] up with the deepest meaning of comedy.” This passage is worth quoting at length:

This art form which is designed to stir the modern audience from its cozy emotional anesthesia operates with images of anesthetized persons, acting in a kind of slow-motion disjunction with each other, and gives us an image of action characterized above all by ceremonious and ineffectuality. At this point the Surrealist arts of terror link up with the deepest meaning of comedy: the assertion of invulnerability. In the heart of comedy, there is emotional anesthesia. What permits us to laugh at painful and grotesque events is that we observe that the people to whom these events happen are really underreacting. . . . This is the secret of such different examples of comedy as Aristophanes’ The Clouds, Gulliver’s Travels, Tex Avery cartoons, Candide, Kind Hearts and Coronets, the films of Buster Keaton, Ubu Roi, the Goon Show.12

Taken together, this is an excellent theory of Dark Firesign. As Firesign, discusses in more detail, more than half of the examples Sontag names are directly cited on the Firesign Theatre’s second and third albums. It is also true that the weakly-defined protagonists of the early Firesign albums, with the possible exception of Nick Danger, can be understood as “anesthetized persons” who are “really underrating.” (No doubt this is why Dave Marsh freaked out!) This is what it would mean to make comedy which, after the losses and disappointments after 1968 did not pretend they were not happening.

“There is something comic in modern experience as such,” Sontag concluded, “precisely to the extent that modern experience is characterized by meaningless mechanized situations of disrelation.”13 That the Firesign Theatre made a comedy representing that disrelation, but which was understood intuitively by its audience as an occasion to listen to it collectively, might be the greatest achievement of their early albums. After reading this recent suite of essays on Surrealism’s centenary in the Brooklyn Rail, I’ll be looking for comedy like that over the next four years.

one more thing

If you’ve read and liked Firesign: The Electromagnetic History of Everything as Told on Nine Comedy Albums, please consider giving it a favorable review on Amazon or Goodreads. I’m told that it’s important, and I would be grateful!

Ed Ward, New York Times (Feb. 6 1971).

Robert Christgau, “New Kind of Comedy Served on a Platter,” Newsday (March 3, 1974); Greil Marcus, “The Firesign Theatre,” The Rolling Stone Record Guide, ed. Dave Marsh and John Swenson (New York: Random House/Rolling Stone Press, 1979) 129–30.

Richard C. Walls, rev. of Waiting for the Electrician or Someone Like Him by the Firesign Theatre, Creem (Nov. 1969).

Richard C. Walls, rev. of How Can You Be in Two Places at Once When You’re Not Anywhere at All by the Firesign Theatre, Creem (Nov. 1969).

Ed Ward, “Through Tirebiter’s Television.” Rolling Stone (Oct. 15, 1970).

Dave Marsh, rev. of I Think We’re All Bozos on This Bus, by the Firesign Theatre, Creem (Nov. 1971).

Neill, rev. of I Think We’re All Bozos on This Bus, by the Firesign Theatre, International Times (Jan. 27, 1972).

Barbara Garson, “Luddites in Lordstown,” Harpers (June 1972); Bud Scoppa, “Los Lobos: 30 Years of Eclectic Rock,” Paste (June 1, 2004).

Susan Sontag, “Happenings: An Art of Radical Juxtaposition,” Against Interpretation (New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1966) 264.

Sontag 268-9.

Sontag 269.

Sontag 271-3.

Sontag 274.

Do you have any evidence to suggest that the Firesigns were aware of the Situationists? Much of what you're describing reminds me of Guy Debord's concept of "detournement".