Gary Usher's Firesign Theatre

when Firesign auditioned to be the theatrical wing of the Wrecking Crew

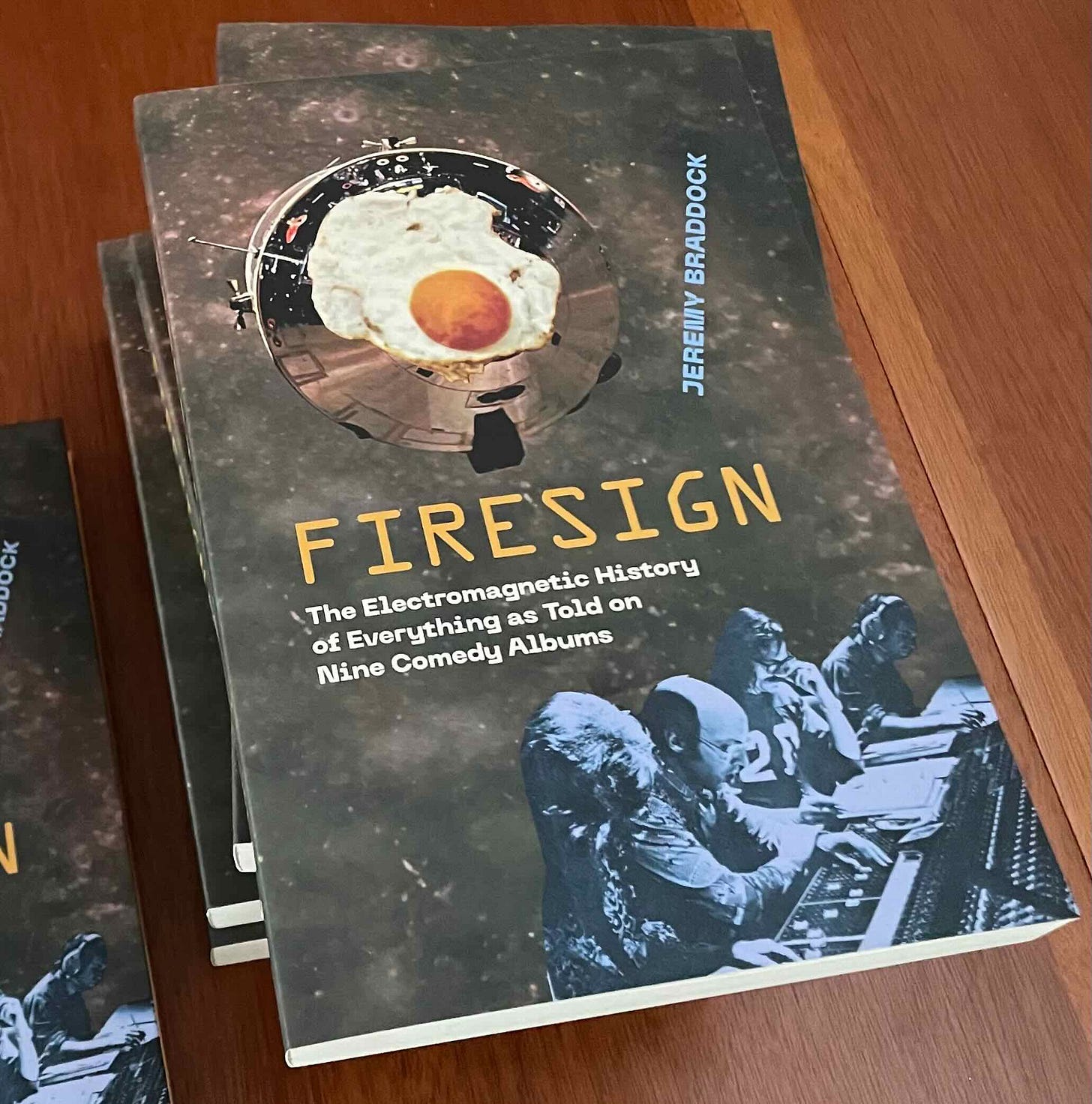

Advance copies of Firesign arrived at my doorstep yesterday, and they look really nice. The release date is October 29, but it looks like advance orders are going out already: the last pocket of unhip resistance will soon be out-of-sight (God, what an awesome moment!). Here’s a link to the book at the University of California Press. Huge thanks to all who have already ordered.

I didn’t end up talking about Gary Usher as much as I thought I would in last week’s post on the Love-In, so this week I thought I’d focus on Usher’s unusual career, and in particular on the short but fruitful period during which he signed the Firesign Theatre to Columbia and produced their first album. Usher’s 1967-68 discography says much about the LA scene circa 1967, and about the uncertain trajectory of the Firesign Theatre before the summer of 1969, when their second album took off.

“[O]ne of the few Californians born in California,” as he described himself, Gary Lee Usher had started in the music business as a songwriter and arranger in the early 1960s, when he formed a sometime partnership with another one of those unusual Californians, Brian Wilson.1 For a decade or more, American pop music had largely run through the New York City and the Brill Building; as leading architects of the new “California Sound,” Usher and Wilson together and separately played major roles in shifting pop’s center of gravity to LA between 1962 and 1966.

Before Brian’s notorious father, Murray Wilson, broke them up, Wilson and Usher co-wrote the Beach Boys’ “409” and “In My Room.” Usher then went on to become one of the leading figures of the surf and hot rod music craze, writing, arranging, and producing an enormous number of records for Dick Dale, the Astronauts, the Rip Chords, the Hondells, the Super Stocks, and (who could forget) Mr. Gasser and the Weirdos, as well as numerous compilations. Many of these were ersatz studio groups staffed by young session pros (including, occasionally, members of the Wrecking Crew).

As these tunes and many others testify, surf and hot rod music was guitar music, driven by the electric guitars and amps coming out of Fullerton from Leo Fender (the Stratocaster debuted in 1954, the Jazzmaster in 1958, and the blackface Twin Reverb amp in 1963).

But it was also, as these examples also show, almost by definition novelty music, with kitsch and comedy elements regularly featuring in the releases. This sensibility persisted into 1966, by which time Usher had a steady gig with Decca Records, where he made a string of records with the Surfaris. It was in this context that Usher first met Phil Austin, an aspiring actor and engineer and Literature and Drama director at KPFK, who (along with two friends) approached Usher about a novelty record that would dispense with the tunes altogether. This record would be the 7” single “Duckman,” a Batman parody in the mode of Stan Freberg’s Dragnet parodies of the 1950s. Shockingly, it was a significant hit and, as Usher’s biographer surprisingly attests, an important release in the producer’s career.2 Within a year, he had moved to Columbia Records, where he would sign Austin, Peter Bergman, David Ossman, and Philip Proctor to record an album as the Firesign Theatre.

Although Columbia had signed the Byrds (at the recommendation of Miles Davis) and Paul Revere and the Raiders, the august label had been late to commit to rock and roll, and it still operated largely out of New York City. Usher was given carte blanche to sign West Coast acts, and for several critical months was the label’s only staff producer in Los Angeles. One of his first assignments was to update the Byrds’ sound, bringing his expertise with modern recording techniques (overdubbing, phasing, and flanging) and arranging experience to mediate the band’s increasingly disparate musical voices.3 The first fruit of this collaboration was the "shining folk-rock, jazz-influenced pop, novelty space rock and colorful psychedelia” of January 1967’s Younger than Yesterday. “While the album's hodgepodge of styles and genres could have easily been a confused mess, Usher's studio command provided the album an impressively uniform consistency.”4

There’s much to say about this great album (as well as Usher’s simultaneous work on Gene Clark’s great album with the Gosdin Brothers, which pointed to where the Byrds would be in a couple of years’ time). But what interests me about Younger than Yesterday is that it can also be understood, surprisingly, as a follow-up to the hot rod novelty tracks of the early sixties and to “Duckman.” This is because Usher and the Byrds can not only be heard to be experimenting with diverse genres, but also with using the new technologies of the multitrack recording studio in an overtly theatrical way.

Exhibit A is the album’s “C.T.A.-102.” For those without headphones, here’s how I describe the track in Firesign:

Roger McGuinn’s paean to a quasar burst believed to be alien communication, “C.T.A.-102” […] begins with two short verses addressed hopefully to the aliens — “Signals tell us that youre’ there / We can hear them loud and clear”—followed by a lengthy twenty-bar solo performed on an electric oscillator triggered by a telegraph key. After one more verse, the music abruptly stops before fading back in through a high-pass filter, as if to dramatize the song’s outer space reception by the aliens, who comment approvingly in tape-speeded interstellar gibberish.5

I’ll talk more about the relationship of this kind of theatricality to multitrack recording next week. But what I want to point out here is that it seems to be no accident that the kitschy fictions of the novelty record — the waves on surf tunes, revving engines on hot rod tunes, the Ghouls’ howling wolf — were morphing into songs containing more fully-conceived imaginary spaces (like the aliens’ outer space reception of “C.T.A.-102”) at the very moment that Gary Usher turned to Phil Austin and Peter Bergman about the possibility of making the album that would turn out to be the Firesign Theatre’s Waiting for the Electrician or Someone Like Him (1968).

It’s the only album they would work on together — the next album would be produced by the Modern Folk Quartet’s Cyrus Faryar (a friend), and all the subsequent records would be credited to themselves and their engineers — but there is no doubt that that Firesign learned a lot from Usher throughout the summer of 1967, or that Usher had a strong hand in that album’s sound. Whereas subsequent records would use needle drops and found sound for their musical cues, for instance, on Electrician these are provided entirely by Glen Campbell and other members of the Wrecking Crew.

This makes it especially interesting that, during the months they were intermittently recording Waiting for the Electrician, Gary Usher was also employing the Firesign Theatre reciprocally as a kind of extra-musical, or theatrical, Wrecking Crew for his other acts. In addition to the notorious Astrology Album (1967) (narrated by Austin, and which I’ll discuss sometime if things get slow), Usher had Firesign produce the tape collage of gun fire and jet fighters that interrupts David Crosby’s pastoral protest song “Draft Morning” on The Notorious Byrd Brothers (1968) — the kind of work Bergman routinely did for his Radio Free Oz show on KPFK. And he had them improvise verbal “media” performances embellishing the high concept “Progress Suite” on Chad and Jeremy’s concept album, Of Cabbages and Kings.

And most notably, Usher had Firesign interpolate a sequence of voices — an evangelical preacher morphing into a military drill instructor — into the middle of “Hotel Indiscreet,” the second single by Sagittarius, the name Usher had given the studio-based project he was pursuing with the collaboration of Campbell and Bruce Johnston as instrumentalists and vocalists.

“Hotel Indiscreet” and its predecessor “My World Fell Down” are some of the strangest pop records you are likely to hear. From one vantage, they are elaborately produced sunshine pop in the vein of the Turtles (but even “sweeter”) they are also often about edgier topics, like sex hotels. Stranger still are the recording experiments Usher was pursuing by himself and with the assistance of the Firesign Theatre. This is especially true of “My World Fell Down,” which devolves after two minutes of eerie sunshine pop into a sound collage of a crying baby, horse race, alarm clock, and bull fight (and nothing else) before a low-key a cappella section leads to a final reprise of the chorus.

Clive Davis was sufficiently alarmed by these experiments as to require new mixes when they were included on Sagittarius’ first album Present Tense (1968), but “My World Fell Down” obtained enough of a cult following as to have been included on Lenny Kaye’s seminal Nuggets compilation (1972) (“original artyfacts from the first psychedelic era”).

But my larger point is that at the moment the Firesign Theatre was beginning to use the multitrack recording studio and the techniques of rock recording to create a new kind of psychedelic (and very literary) comedy was also the moment many musicians were experimenting with creating theatrical (and in some cases literary) worlds with and in their own recordings. I’ll talk more about that next week.

Stephen J. McParland, The California Sound, An Insider’s Story: The Musical Biography of Gary Lee Usher (self-published, 2014) 11.

McParland 162.

Roger McGuinn quoted in Harvey Kubernik, Turn Up the Radio!: Rock, Pop, and Roll in Los Angeles, 1956-1972 (Santa Monica P, 2014) 200-3.

David N. Howard, Sonic Alchemy: Visionary Music Producers and Their Maverick Recordings (Milwaukee: Hal Leonard, 2004) 70,

Jeremy Braddock, Firesign: The Electromagnetic History of Everything as Told on Nine Comedy Albums (Oakland: University of California P, 2024) 38.

Just ordered!

A barely-related aside to this week's post: In May 1974, I was on the stage crew for a college rock concert, Procol Harum, with opening acts Livingston Taylor and Chad Stuart, who'd gone solo during a break from Chad & Jeremy.

Backstage after his performance, I chatted with Chad, and when I asked him about his career, he told me what a horrible experience the early days had been, thrown onto a huge tour when the two of them were way too young. He seemed really bitter about it.

But as I now look over his later career, it looks like he made the best of a varied and wonderful career.