history of the rock-comedy 7", part two

comedy and airplay in the 1970s — the game Cheech & Chong won (and then got tired of winning)

I’m just back from Toronto, where I got to talk about Firesign with colleagues and grad students at York University. It was a great trip and when I got back I learned that Firesign had been awarded a Certificate of Merit by the Association for Recorded Sound Collections, joining some great 2024 books like Liz Pelly’s must-read study of Spotify (Mood Machine), and Rob Drew’s history of the cassette tape. That’s very nice company to be in.

Also, before I start, a couple quick announcements for the hardcore Firesign Theatre fans. First, Firesign’s archivist Taylor Jessen has just announced the discovery of some long-sought Firesign air checks. Two are plays from their 1967-68 run at the Magic Mushroom: the hitherto unheard “Last Tunnel to Fresno” and a second, shorter version of “The Sword and the Stoned.” Also available is a restored (and finally complete) episode of their 1970 KPFK radio program Dear Friends, “A Funny Thing Happened to Me on the Way to the Inquisition.” They can all be streamed or downloaded from the Internet Archive at the embedded links above.

The second offering is an archive of Firesign material compiled by the editor of the legendary 70s fanzines Firemail and Chromium Switch, Tom Gedwillo. According to Tom, included here are “radio shows and interviews (KPFK, KBOO, KPLU, KTLK, KRLA), the Chromium Switch magazine interviews, the Golden Ego Radio tribute to Peter Bergman, the Edgar Letters Collection, selected Radio Free Oz podcasts (including the Daniel Ellsberg interview), the Bill McIntyre video interview, exclusive tour diaries from Phil Fountain and Taylor Jessen, and many others.” Tom’s materials will be accessible until November 23: https://jmp.sh/lla4SOyK.

Now on to the second part of my history of the rock-comedy 7”, a rabbit hole I descended as I was thinking about why the record industry turned its back on the Firesign Theatre, on or about October 1975. The short answer is that radio was changing in ways that made many comedy acts, especially those who viewed themselves as recording acts, understand that they now needed to have a musical single to get airplay.

I started part one with Bill Cosby and ended with Cheech and Chong’s fantastic-sounding run of early 70s singles (every one of which charted). Although they always affirmed their roots in the underground counterculture, Cheech and Chong understood better than anyone else that their records increasingly had to swim in the waters of an increasingly corporate FM radio — and its new AOR format — as the decade wore on.

We’ll visit them again here, picking up on the duo’s strange, and unfortunately still very timely, relationship with Bruce Springsteen. But first let’s look at the broad field of acts that tried to ride the tiger that they, for a while, had tamed.

3. The Credibility Gap

The Credibility Gap was an LA-based comedy group with an unusual and complicated history. They first came together on KRLA-AM, the big market pop station that had hyped the Beatles in 1963 and four years later lured Peter Bergman’s Radio Free Oz away from KPFK, just as the Firesign Theatre was also signing a deal with Columbia Records. Brainchild of KRLA news director Lew Irwin, the Credibility Gap was at first set up to provide satirical commentary on the day’s events, work that was represented on their sui generis LP, An Album of Political Pornography (1968). By 1970 the Gap had moved, along with Firesign, to the commercial freeform station KPPC-FM, keeping only Richard Beebe from the original cast and adding three new members: Michael McKean, Harry Shearer, and David L. Lander. They continued to work as satirical newsmen, now sometimes composing topical songs they would perform with the day’s broadcast. Their next album, Woodshtick and More (1971), was a more conventional comedy record that imagined the Woodstock festival as a gathering of borscht-belt comedians in the Catskills. It was a bad idea, and they were soon dropped by their label, Capitol Records. Later in the year, they and the rest of the KPPC staff were summarily fired as the station abruptly abandoned its freeform format (c.f. the story in part one about Detroit’s WABX).

But in 1973, Warner Bros. took a flier on the Credibility Gap and the group responded with the smart and funny Jesus Christ Superstar parody “Something For Mary,” featuring Renee Plant in the title role: “Good morning, Joseph / You’re looking fine / Good morning, Joseph / Let me lay it on down the line.” That 7” previewed the less good 1974 album A Great Gift Idea, which included more musical parodies (among them a regrettable sketch about Sly Stone). McKean and Shearer would finally find surer footing in the eighties, when they joined the National Lampoon’s Christopher Guest and several combustible drummers to form Spinal Tap.

4. The National Lampoon

National Lampoon was the group that pursued rock-comedy glory most assiduously after Cheech and Chong, although “group” is not really the most apt term to use. The National Lampoon was something more like a franchise, a brand for a few kinds of satirical white humor that began with the magazine (a spin-off of the Harvard Lampoon), and extended to a syndicated radio program, several albums, a Broadway musical, and then a slew of mainstream movies that are as good a guide as anything to the Reagan years. Many seventies stars got their start with the Lampoon, including a lot of the first cast of Saturday Night Live. Their twilight years have elicited quite a bit of self-regarding hagiography which seems the fitting capstone to the (now) confusing air of superiority that had been the magazine’s calling card from the beginning.1 They helped give us Gilda Radner, but I still kind of hate them.

As with their theatrical Woodstock parody Lemmings (1973), which itself spawned a soundtrack album, the Lampoon’s early LPs are obsessively concerned with rock music culture. But whereas Cheech and Chong’s early singles understand the feel of the records they’re sending up, and express affection for it, the Lampoon parodies are all tinged with a kind of aggressive envy, and don’t sound nearly as good as their sources, which is an obvious problem.

An exception where the aggression actually works is Tony Hendra’s brutal send-up of primal scream-era John Lennon (“Magical Misery Tour”), which took its lyrics from Lennon’s notorious 1970 Rolling Stone interview, and was the standout track on their first album, Radio Dinner (1972). More characteristic are the record’s nihilistic parodies of the other ex-Beatles: Paul is assassinated each time he begins to sing “Give Ireland Back to the Irish,” while George’s benefit concert and album for Bangladeshi refugees (1971) provides the excuse for a long sequence of racist one-liners and (I’m not kidding) smug starvation jokes. Weirdly, Radio Dinner’s one single parodied a sanctimonious, and now lost to history, easy-listening/spoken-word track titled “Desiderata,” the parody succeeding in being as exactly as annoying as the original.

Lampoon’s second single was pulled from Lemmings, whose off-Broadway run featured Chevy Chase on drums, John Belushi on bass, and Christopher Guest (who also wrote the music) on guitar. Curiously passing over the impressive CSNY parody “Lemmings Lament” and the Iron Butterfly jam “Megadeath” (from which the real metal band would take its name), the song chosen to promote Lemmings was a mildly vertiginous parody of 1950s nostalgia (Sha Na Na played Woodstock, remember) called “Pizza Man.” It has exactly one joke — Alice Playten’s hiccups on the turnaround — but that joke is pretty funny.

But as we saw in part one, it was not until around 1973 (mirabilis annus “Basketball Jones”) that the rock-comedy 7” fully appeared as a distinct genre. Accordingly, Lampoon’s first fully committed contribution to the genre appeared with 1975’s “Kung Fu Christmas,” a pastiche of Philly soul written by Brian Doyle-Murray and Paul Shaffer. Possibly an attempt to cash in on Cheech and Chong’s “Santa Claus and His Old Lady,” “Kung Fu Christmas” is a high-production extension of the earlier records’ touristy racism. The album it promoted, Goodbye Pop 1952-1976, includes Guest’s minor but great “History of the Beatles.”

“Goodbye Pop” would have been a good pseudonym for the Lampoon’s reactionary final single, “What Were You Expecting (Rock ’n’ Roll),” a finger-wagging medley of late 70s genre pastiches, from reggae to Springsteen, whose originals had the temerity to call themselves Rock. The corresponding LP (White Album, 1980) depicted Klansmen on both sides of the glass of a recording studio. As the last track on the record, “What Were You Expecting” begins with a plausible twenty-second Devo parody, but it’s downhill from there.

5. Monty Python

In some ways, Monty Python would seem to have been perfectly positioned to make a string of rock-comedy singles. Their BBC Television run (1969-1974) maps almost exactly onto the early years of the genre, with the first of their LPs appearing in 1971 (the year of Cheech and Chong’s first single and I Think We’re All Bozos on This Bus). Python also had hugely committed fans in the British rock scene. Pink Floyd, Led Zeppelin, and Jethro Tull’s Ian Anderson would all help to bankroll the classic film Monty Python and the Holy Grail (1975) and George Harrison would be a key backer of the follow-up, Life of Brian (1979). And they had a key collaborator in Neil Innes, co-founder of the late-60s avant-garde-comedy-jazz-rock group The Bonzo Dog Doo-Dah Band. Innes performed and wrote songs for Python (“Brave Sir Robin”) and later formed Beatles parody group The Rutles with Python’s Eric Idle.

But although Python was hip comedy, Python themselves were not very hip. Despite their contacts and contemporaneity with the peak of British rock, and the topicality of their other humor, Python almost programmatically ignores rock music. Their first three singles — appearing the year of Pink Floyd at Pompeii (1972) — comprised two light novelty songs (“Eric the Half a Bee” and “Spam”) and a light political satire in the form of a language-instruction record (“Teach Yourself Heath”).

The one exception was not released as a single. Side two (or three2) of The Monty Python Matching Tie and Handkerchief (1973) begins with a parody of a BBC public interest program (“Background to History”) in which a panel of scholars answer questions about medieval agrarian history in the mode of several convincing and funny pop songs written by Innes. After a reggae number and a Gary Glitter rave-up, the sketch culminates in an ecstatic “Hey Jude” parody: “Oh it’s written in the village rolls / That if a plow team wants an oxen / And that oxen is leant / Then the villeins and the plowmen got to have the lord’s consent ! (Nana na na! Nana na na!).” It sounds great, and is one of the best points on their best album, but because it’s not a single song, would not have been a good candidate for a Radio 1 or WMMR playlist.

6. Charlie Drake

Here’s a crazy one I only just learned about from the Fairport Convention episode of Andrew Hickey’s History of Rock Music in 500 Songs.3 Charlie Drake was a slapstick comedian who had gotten his start a child performer in prewar London music halls and became a fixture of postwar British TV and film. Starting in the late 1950s, he also recorded a string of singles with Parlophone’s George Martin (“My Boomerang Won’t Come Back”), Martin’s pre-Beatle work having largely been comedy recordings.

Somehow connecting with Peter Gabriel, who had just left Genesis, Drake later cut the 1975 single “You Never Know,” a record that splits the difference between the singalong style of the historic music hall with the mid-decade British prog that would sometimes reference it (e.g. “Killer Queen”). He was supported by an all-star band that almost rivals the one Cheech and Chong assembled for “Basketball Jones”: Gabriel and Sandy Denny on backing vocals, Phil Collins on drums, Robert Fripp on guitar, Brian Eno on mellotron, and Keith Tippett on piano. Drake would release one more single, “Super Punk,” which appeared in January 1977, two months before the Clash’s debut single “White Riot.”

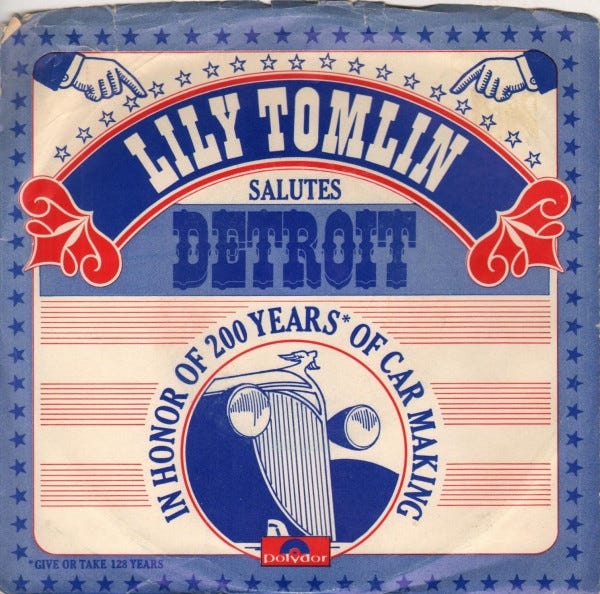

7. Lily Tomlin

Because Lily Tomlin is apparently capable of doing anything, recordings are only a small part of her career (I especially recommend her 1975 LP Modern Scream). Neither needing nor exceedingly interested in rock music, Tomlin nevertheless released two non-album musical singles in the early seventies, both of which seem very interesting (I haven’t been able to find them online). The first was a 1973 cover of Noël Coward’s grimly comic “Twentieth-Century Blues” (1931), its sleeve displaying a deli-wrapped piece of horse meat. That was followed by “Detroit City,” a Motown-styled ode to her hometown that expresses defensive outrage at scaremongering discourse about the post-’67 Motor City, while at the same time managing jokes about its pollution, poverty, and strawberry milkshakes. Tomlin performed a version of the song (with dance moves) on one of her Emmy-winning television specials in 1975. The Motown label had moved to LA three years earlier.

8. Martin Mull

Like Tomlin (but unlike everyone else discussed here), Martin Mull does not seem to have been especially invested in rock music. But he was a competent multi-instrumentalist (piano, guitar, ukulele) whose television and stage act included dozens of self-penned songs some of which definitely belong to the seventies’ rock-comedy genre. It’s a considerable feat considering that he could barely sing.

Each of Mull’s nine singles is at heart an ingratiating show tune, whether he is working in the vein of Randy Newman (“In the Eyes of My Dog,” 1973), wedding-band r&b (“Do the Dog,” 1975), or, inevitably, disco (“Get Up, Get Down,” 1977; “Bernie Don’t Disco,” 1979). His most durable recording would be the 1973 Curtis Mayfield pastiche “Santafly,” a Christmas song which, getting the jump on the National Lampoon, uses Black music as both source and object of its season-specific comedy.

Much to his surprise (I’m sure), Martin Mull would later be vested with a massive sum of rock-comedy credibility when, at the very peak of their influence, Sonic Youth recorded a cover of Mull’s 1972 non-album promo 7” “Santa Claus Doesn’t Cop Out on Dope” for the mid-nineties Christmas compilation Just Say Noël. Like their covers of Madonna’s “Into the Groove” and the Carpenters’ “Superstar,” it deformed the original in a way that still expressed appreciation for it.

9. children of SNL

And then Saturday Night Live changed the rules of the game. Starting in 1975, with its weekly spot for musical guests and space for solo comedians, SNL regularly brought hip comedy and popular music into each other’s ambits in a way that had not been the case since the explosion of the Rock Industry had moved big acts out of the clubs and into large theaters, arenas, and stadiums. Television’s new hospitality, meanwhile (the first HBO stand-up specials also began in 1975), meant that hip comedians could choose to be less reliant on radio and records — including the 7” single — as a means of exposure.

For cast members, SNL was itself a space for enacting rock ’n’ roll fantasies, licensing the records that followed. Most famous of course was John Belushi and Dan Aykroyd fictional white r&b act, The Blues Brothers. Debuting on SNL on April 22, 1978, and soon to add an expert backing band — Steve Cropper and Donald “Duck” Dunn of Booker T. and the MGs, Matt “Guitar” Murphy, drummer Steve Jordan, the horns from Blood, Sweat and Tears — the Blues Brothers would go on to release three albums and five singles, as well as a blockbuster movie. Though the records are all compromised by Belushi’s weak and humorless singing, it is still worth hearing the group’s 1978 cover of the novelty doo-wop track “Rubber Biscuit,” their only track that qualifies as a rock-comedy 7”.

Amazingly, the same episode of Saturday Night Live that saw the Blues Brothers’ debut also saw the premiere of guest host Steve Martin’s novelty single “King Tut,” which reached #17 on the charts later that year.4 A smarmily congenial satire of Treasures of Tutankhamun — the Led Zeppelin of museum exhibitions — Martin’s mid-tempo banger was the perfect complement to his stand-up style, which employed the catchphrase in a way that has been compared to the broad gestures of arena rock5 (it’s easy to imagine the “Born in Arizona / Moved to Babylonia” refrain banging off the back wall of a civic center). Martin recorded the 7” backed by members of the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band, an act he’d opened for on the way up. At several amphitheater shows in 1978, the Blues Brothers opened for him.

But by far the most interesting and edgy of the SNL rock forays was the new wave band invented and fronted by Gilda Radner in 1979, Candy Slice and the Slicers. The Slicers performed on two separate SNL episodes in 1979, and reprised their two songs for Radner’s one-woman Broadway show, recorded for her album Live From New York (1980). Though Patti Smith is Radner’s obvious model, Candy Slice is a character with a life beyond the parody, and the band (featuring Paul Shaffer on drums!) is completely simpatico. Radner understood how punk rock would take pleasure in defiant self-abasement, and saw the way — especially for women-led bands like the Slits or the Plasmatics — punk provocations were often already a kind of comedy, especially for those inside of it. Hence the connection Greil Marcus saw between punk and Dada, and hence Candy’s immortal lines, which you have to hear as well as read: “If you look closely / You can see my tits / Because I want you to but don’t want you to KNOW THAT I DO!”

Stupidly, Warner Bros. passed over Candy Slice and chose the ingratiating “Honey (Touch Me With My Clothes On)” as Live from New York’s single, and it tanked. But if there was ever any doubt that Candy Slice and the Slicers could have passed the smell test at CBGB, please note Olympia punk band Rik and the Pigs’ sympathetic cover of the Slicers’ “Gimme Mick,” recorded as a 7” b-side in 2016. I know Fred Armisen was in Trenchmouth, but Gilda Radner is still the punkest SNL would ever be.

10. Cheech and Chong 2

When we left Cheech and Chong in part one, they had just released two singles from their Wedding Album (1974). “Earache My Eye” reached the Billboard top ten, and its follow-up “Black Lassie,” a relative disappointment at #55, was still solidly in the Hot 100. But the back half of the decade saw them making the jump to movies, beginning with 1978’s Up in Smoke. Along with the realignment caused by SNL (which appears never to have invited them), the move toward film may explain the lack of effort evident in the rest of their recorded oeuvre. Most are parody covers, from the Coasters’ “Framed” (1976), to the Floaters’ “Float On” (“Bloat On” [1977]) and a British punk “Rudolph the Red Nosed Reindeer” (1977). It’s hard to imagine them getting airplay.

But they had one more card to play when Cheech Marin rewrote the title song of Bruce Springsteen’s Born in the USA (1984) as “Born in East LA.” Far from breezily celebrating his neighborhood roots, Cheech’s new lyrics rewrote Springsteen’s post-Vietnam parable as a song about ruthless, corrupt immigration enforcement. “I was born in East LA” are the words of a birthright citizen addressing an INS agent who deports him anyway. The rest of the song is (if you can imagine such a thing) Cheech and Chong’s musical comedy version of El Norte: “I crawled under barbed wire, swam across a stream / Rode in six different trucks packed like a sardine / Walked all day in the burning sun / Now I know what it’s like to be born to run.” It’s the last (but one) of Cheech and Chong’s comedy-rock singles, and the first of the genre to have a video in rotation on MTV (bellwether of another realignment, this one post-SNL).

A few months ago the Boss told an audience in Manchester UK about a government “removing residents off American streets and, without due process of law, […] deporting them to foreign detention centers and prisons.”6 I wonder if he would consider inviting Cheech and Chong — who after all helped give him his start7 — to perform their rewrite of “Born in the USA” on any upcoming American dates.

11. Bob and Doug McKenzie

If, as Robert Christgau said, Cheech and Chong repurposed drunk humor and ethnic humor for a mass audience of stoners,8 Rick Moranis and Dave Thomas’s Bob and Doug McKenzie characters were a kind of dope humor in the key of beer, “Canadianness” replacing Mexican and Chinese on the slippery slope of ethnic humor. I’m sure the reference was intentional.

I’m not sure what it says about me that I love this record. Having started on SCTV as a parody of a Canadian cable access show, The Great White North (1981) finds Bob and Doug extending their schtick to the process of making a record, which forms the loose narrative comprising drinking games, coffee sandwiches, church sermons (L. Ron McKenzie), frostbite, and Thomas’s impressive talent for Foley. Their Cheech and Chong tribute extends to the album’s two comedy-rock singles, one of which is a travesty of “The Twelve Days of Christmas” that somehow doesn’t manage to get to day twelve. The other song — “this is the hit single part of our album, good day” — features guest vocals from Geddy Lee of Rush, who admirably enters into the spirit of things: “it’s my pleasure … ten bucks is ten bucks … I’m a professional, eh?”

I can remember hearing it on the radio, but “Take Off” is conspicuously low-rent, Geddy doing his spirited best on a track that would otherwise seem to belong on a cable television lifestyle show. Broken Social Scene has yet to cover it. But even on this track you can hear the meticulous production that went into this apparently off-hand record: from each perfectly-timed bottle cap bouncing along the floor to the cavernous echo of the “Take Off” recording studio, it’s a fitting valedictory to the age of the comedy concept album.

12. Eddie Murphy

After Bob and Doug came to praise the rock-comedy 7”, it fell to Eddie Murphy bury it, and then transcend the form entirely. He had been the breakout star of Saturday Night Live’s troubled second wave, and unlike the SNL’s original cast (which had come up in improv), Murphy’s roots were in stand-up and he maintained that part of his career even as he valiantly kept SNL on life support. That led to two early eighties concert albums, the first of which, Eddie Murphy (1982), appended two musical singles, each of which exhibited the homophobia that was Murphy’s unfortunate hallmark in the early years of the AIDS crisis (his Wikipedia page states that he has since donated to AIDS charities). The first single was the penetration-curious rap pastiche “Boogie in Your Butt” (it was later released as a 12”). The second was a truly odd cover of the Barbra Streisand/Donna Summer empowerment-themed disco track “No More Tears (Enough is Enough),” which Murphy staged as a duet between his SNL character Buckwheat and the camp fitness guru Richard Simmons.

Murphy went on to film two stand-up specials (Delirious and Raw) before jumping to mainstream cinema, where he became one of the biggest stars of the eighties. That stardom led to a surprisingly successful mid-decade vanity project: three albums of more-or-less straight-ahead pop r&b songs. Though subject to the law of diminishing returns, the first of them (How Could It Be, 1985) produced a great single, the Rick James-penned “Party All The Time,” which went to #2 in the fall of 1985.

The Rest is Yankovic

Of course in the mid-1980s there were other things afoot. The redoubtable (and confirmed Firesign Theatre fan) Weird Al Yankovich had begun his string of parody covers with the accordion-only “My Balogna” in 1979. In 1983, his self-titled debut album — produced by Rick Derringer of “Rock and Roll, Hoochee Koo” fame — elicited three singles: “Another One Rides the Bus,” “Ricky” and “I Love Rocky Road.” It worked out well. Culminating (but not concluding) a long and resilient career, Weird Al played a well-publicized show at Madison Square Garden this summer. Also this year, we saw the return of the comedy metal band Spinal Tap, who broke like the wind just after Weird Al with the 1984 singles “Christmas with the Devil” and “Hell Hole.”

It is notable that with these two acts the songs are no longer in the service of other work; the band itself has become the joke. On one hand, this seems evidence of a world in which comedians are no longer able or interested in exploring recording as a medium. But that may in turn be testimony to the way music and comedy, visionary or otherwise, have been kept separate at a higher, industrial level. There is no recommendation algorithm that will feed you “I Want You (She’s So Heavy)” after “Basketball Jones,” even though both tracks have the same guitarist and organist.

“‘What we do is oppressor comedy,’ is the proud claim of Lampoon Editor in Chief P.J. O’Rourke, 30. […] ‘Our comic pose is superior. It says, “I’m better than you and I’m going to destroy you.” It’s an offensive, very aggressive form of humor.’” “Show Business: The Lampoon Goes Hollywood,” Time (14 Aug. 1978) https://time.com/archive/6880101/show-business-the-lampoon-goes-hollywood/ <Accessed 31 Oct. 2025>.

It depends on where the needle drops. This side of the album notoriously contains two parallel grooves.

Andrew Hickey, A History of Rock Music in 500 Songs, Song 178: “Who Knows Where the Time Goes” by Fairport Convention, Part Two: “I Have No Thought of Time” (23 June 2025) https://500songs.com/podcast/song-178-who-knows-where-the-time-goes-by-fairport-convention-part-two-i-have-no-thought-of-time/ <Accessed 5 Nov. 2025>.

Doug Hill and Jeff Weingrad, Saturday Night: A Backstage History of Saturday Night Live (New York: Beech Tree, 1986) 296-98.

Jacob Smith, Spoken Word: Postwar American Phonograph Cultures (Berkeley: U of California P, 2011) 196.

https://brucespringsteen.net/news/2025/land-of-hope-and-dreams/ <Accessed 9 Nov. 2025>.

http://brucebase.wikidot.com/gig:1972-10-28-hollinger-field-house-west-chester-pa <Accessed 9 Nov. 2025>.

Robert Christgau, “The Comedy Album Crop,” Newsday (11 Mar. 1973) https://www.robertchristgau.com/xg/news/nd730311.php <Accessed 10 Nov. 2025>

Martin Mull parodied a number of different styles, most effectively (in my opinion) Bossa nova and gospel. When I think of him and rock though it's always "Licks Off Of Records." His singing was part of the parodies.

These last couple entries were a book in themselves! So good. Thanks for continuing it all.