she feels as if she's in a play

When pop music performed a media archaeology of radio drama

Happy Friday, all. It was fantastic this week to see copies of Firesign reaching the mailboxes of friends who read chapter drafts over the years, and generally indulged me as I plunged down many, many rabbit holes: thank you!

I also did a short interview for the Cornell Chronicle this week; you can read it here.

Last week I was talking about the producer Gary Usher and his experiments with theatrical effects recording the Byrds and others in 1967 (one more of these is discussed below). Creating theatrical space — or diegeses — inside studio-recorded pop songs was the obverse of what the Firesign Theatre was at the same time beginning to do: using the technologies and technologies associated with the new rock music to create a form of psychedelic radio drama. It’s no accident Usher employed them to help dramatize his other Summer of Love recordings.

In today’s post I’m going to argue that these records were part of a more general tendency in pop recording that emerged with the expansion of multitrack recording at the end of the 1960s and, more surprisingly, owed more than a little to the cultural memory of “golden-age” radio drama, then only a short decade in the past.

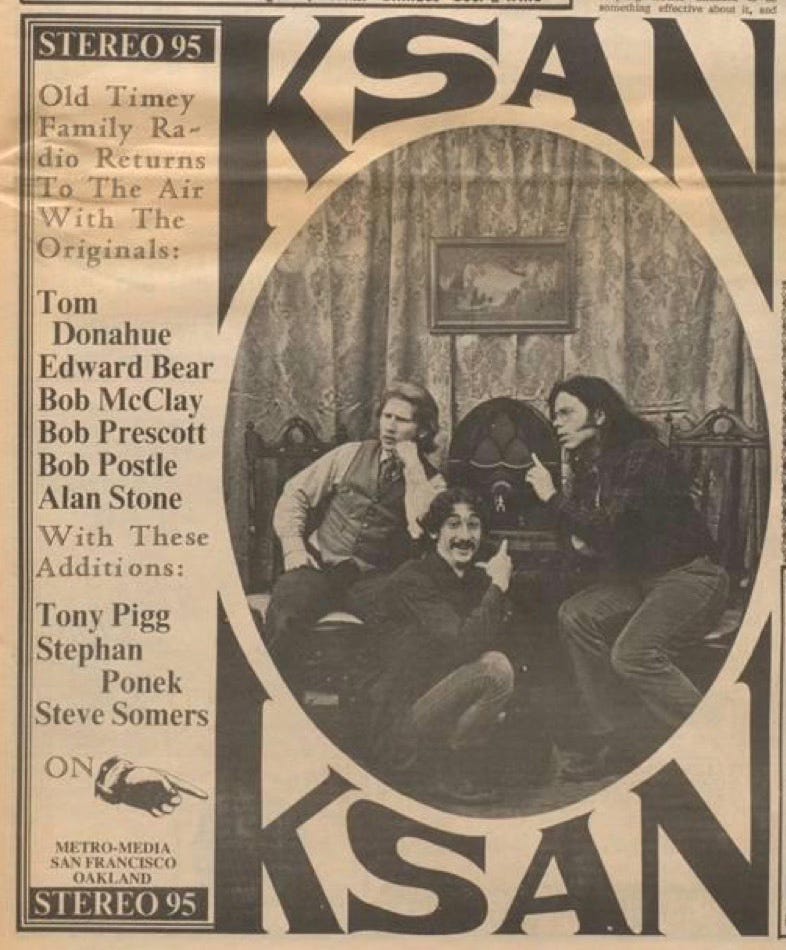

When I was working on the “radio” chapter of Firesign, I read several memoirs of DJs who worked for FM stations during the vaunted freeform/underground days (1967- 1971 or so), and I was surprised to see how many of them described their work as a revival of the “theater of the mind” radio drama of the 1930s and 40s.1 And this was probably not only a retrospective assessment: a May 1968 ad for San Francisco’s KSAN (featuring in-house Firesign Theatre clones Congress of Wonders) openly encouraged the association of freeform broadcasting with “old timey family radio.”

Arguably, the DJs were only catching up (as usual) with the Beatles who had made a similar and more avant-garde connection a year before the FM revolution began. Driving back to Liverpool from London one night in 1966, Paul McCartney heard Martin Esslin’s production of the Alfred Jarry play Ubu Cocu on the BBC’s Third Programme, discussing it enthusastically in interviews later in the year. By the end of the year McCartney had developed the idea of an album featuring a fictional Lonely Hearts Club Band, introduced by the theatrical effect of a crowd hubbub and tuning orchestra.2 The Firesign Theatre had an early mix of Sgt. Pepper with them in the studio as they recorded Waiting for the Electrician, and they would draw extensively both from the popular avant-gardism of the Third Programme and the commercial radio dramas of the 1940s.

Such theatricality, though, was only a more thorough elaboration of techniques that had accompanied pop music since the early 1960s, when multitracking began to untether the concept of a pop song from the concept of a live performance. What follows is a short — and definitely incomplete — genealogy of multitrack theatricality in pop music.

If we’re talking about pop music as radio drama, there is no one more dramatic than the Shangri-Las, who incorporated diegetic effects on their back-to-back top 5 singles of 1964, “Remember (Walking in the Sand)” and “Leader of the Pack”? The Shangri-Las repeatedly used sound effects and voice-over narration placing listeners in a highly theatrical space (see also “Maybe” and “I Can Never Go Home Anymore”). I can’t resist posting live appearances here (not least for the verité effect of the motorcycle rider), but note that these are lip-synced appearances and the revving engines, waves, and sublime seagulls are all features of the recordings.

Meanwhile, on the west coast, Brian Wilson and Gary Usher were each in their own ways working to expand the California Sound the they had helped invent as collaborators early in the decade. The two years before The Beach Boys’ masterpiece Pet Sounds (1966) are filled with semi-successful experiments that in retrospect are fascinating roads not taken. I’ve always been interested in a minor track on 1965’s Summer Days (And Summer Nights!!). In one respect a novelty song in the vein of “Salt Lake City” or “Drive-In,” “Amusement Parks U.S.A.” is notable for its instrumental break which pipes in screams of roller coaster riders and half-convincing scripted performances of carnival barkers (hurry hurry hurry step right up folks to The Beach Boys’ Circus) and fairgoers over Brian’s electric organ vamps, which suddenly sounds like it could belong both to the band’s backing track and at the same time belong to the imaginary world of the amusement park conjured by the sound effects and dialogue — a degree of ambiguity that is certainly the most exciting thing about the record.

Given this context, though, it’s hard not to wonder if “Amusement Parks U.S.A.” was the inspiration for the sound effects and naval nonsense dialogue placed in the corresponding section of the Beatles’ “Yellow Submarine” (1966).

Gary Usher was no doubt aware of all of these examples as he worked throughout the summer of 1967 on recordings by the Byrds, Chad and Jeremy, Sagittarius, and the Firesign Theatre. Andrew Hickey has noticed one further example of this kind of theatrical experimentation in Usher’s uncredited production of “Fakin’ It” on Simon and Garfunkel’s Bookends album (1968), a song that begins and ends with a citation of “Strawberry Fields Forever” and includes an exchange of dialogue that is a dream-like staging of Paul Simon’s lyric:

Prior to this lifetime, I surely was a tailor

Look at me

(spoken, Beverly Martin: Good morning, Mr. Leitch

Have you had a busy day?)

I own the tailor's face and hands

I am the tailor's face and hands

I know I'm fakin' it.

These kind of mini fictions would become increasingly common on records in the late sixties and early seventies. I would be remiss if I didn’t shout out what I think is the first example (with many to follow) from Pink Floyd. Recorded at exactly the same time, Floyd’s “Alan’s Psychedelic Breakfast” uncannily resembles the introduction of Firesign’s George Tirebiter fumbling through his refrigerator eight minutes into Don’t Crush That Dwarf Hand Me the Pliers.

Another place where popular musicians would use multitracking to embed theatrical effects and diegetic space into songs was in hip-hop music, especially the sample-based records of the genre’s late 80s-early 90s “golden age.” Here are a couple of my favorites: Big Daddy Kane and Ice Cube inviting Flavor Flav and Chuck D. to go to the movies in “Burn Hollywood Burn” (1990) (Chuck off mic: “Now you know how I feel about giving these movies my money […] all this Steel Magnolias shit”); Posdnous and Dave from De La Soul as muppet babies at the beginning of Queen Latifah’s “Mama Gave Birth to the Soul Children” (1989).

Like other records from the era, De La Soul’s first record Three Feet High and Rising (1989) contained numerous skits linking and sometimes interrupting its tracks. When Greg Tate reviewed Three Feet High and Rising for the Village Voice, he said it extended the tradition of Parliament-Funkadelic, Sly and the Family Stone, and the Firesign Theatre.3

Next week, I’ll talk about the thirty-year history of hip-hop DJs sampling the Firesign Theatre — which was one of the most fun and interesting things to track down as I was writing my book. For now, I’ll leave you with a track by the Last Poets, an act that was contemporary with Firesign, and a forerunner to the revolutionary rappers of the 1980s. Of all the tracks I’ve linked to here, “On the Subway” (1970) is the one that is closest to being a radio drama in its own right, as Alafia Pudim’s monologue — about a white man refusing to make eye contact on the subway — is dramatized by the Foley-like conga and vocalizations making the sound of the train and the other Last Poets’ background performances as the white guy (including his eyes blinking) and the conductor’s announcement, which satisfyingly conclude: “Next stop, 125th Street.”

This is an abbreviated genealogy, and I know I’ve left out a lot. Tell me your own favorite examples of pop song diegeses in the comments below.

Richard Neer, FM: The Rise and Fall of Rock Radio (New York: Villiard, 2001) 77; Dave Pierce, Riding on the Ether Express: A Memoir of 1960s Los Angeles, the Rise of Freeform Underground Radio, and the Legendary KPPC-FM (Center for Louisiana Studies, U of Louisiana Lafayette, 2008) 321; Wes "Scoop" Nisker, If You Don’t like the News … Go Out and Make Some of Your Own! (Berkeley: Ten Speed P, 1994) 49-50.

Steve Turner, Beatles '66: The Revolutionary Year (New York: Ecco, 2016) 56-57, 102, 119.

Greg Tate, "Yabba Dabba Doo-Wop: De La Soul," Flyboy in the Buttermilk: Essays on Contemporary America (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1992) 140.

Great thread! What sprung to my mind first for audiodramatic pop records was the novelty songs of the Coasters. Googled who produced those records - it was Leiber and Stoller, who were also responsible for "Leader of the Pack". An even earlier record of theirs with audio effects is 1954's "Riot in Cell Block #9" by the Robins, which opens with a siren and machine gun sounds. (The Beach Boys later adapted that song, including a siren sound effect, as "Student Demonstration Time" on 1971's "Surf's Up" album.) Somehow I thought Leiber and Stoller were part of the Brill Building/New York scene, but they were actually based out of Los Angeles!

Maybe the most famous rock 'n' roll diegetic opening is The Rolling Stones' "She's a Rainbow" - "...one spin and one spin only!"